Melbourne’s second major river, the mighty Maribyrnong, runs for 160 kilometres from its source on the slopes of Mount Macedon through to Port Phillip Bay.

Get to know the river:

History

Maribyrnong River’s name comes from the Aboriginal phrase Mirring-gnay-bir-nong, meaning ‘I can hear a ringtail possum’. It was originally called Saltwater River due to the seawater that entered from Hobson’s Bay, into which it directly flowed.

The Wurundjeri people have always had a deep connection to the area. The river was of great importance and used for a variety of purposes:

- drinking water

- building material

- transport

- medicine – including edible plants that grew on the river flats

- food – fish and eels thrived in the river, and big game like kangaroos and emus lived on the plains, along with smaller animals like echidnas, possums, lizards and water birds.

In 1857 Victoria’s first irrigator, David Milburn, settled in the area. He developed a way to draw water from the river using a hand pump, and grew fruit and vegetables to sell to diggers travelling to the goldfields. This was the start of Keilor’s market gardening tradition, which continued until 1983.

From the mid-nineteenth century the suburb of Footscray turned into Melbourne’s industrial powerhouse – subjecting the river to severe environmental degradation, until manufacturing declined in the 1960s and 70s. Today these industrial closures are prime development opportunities that drive the area’s regeneration, offering a waterside location close to central Melbourne.

Did you know? Shark and dolphin skeletons have been found under Maribyrnong Park, and oyster and other shells at Steele Creek.

Natural features

The Maribyrnong gradually changes along its length:

- from a small headwater stream

- to a lowland river

- to an estuary where it meets the sea.

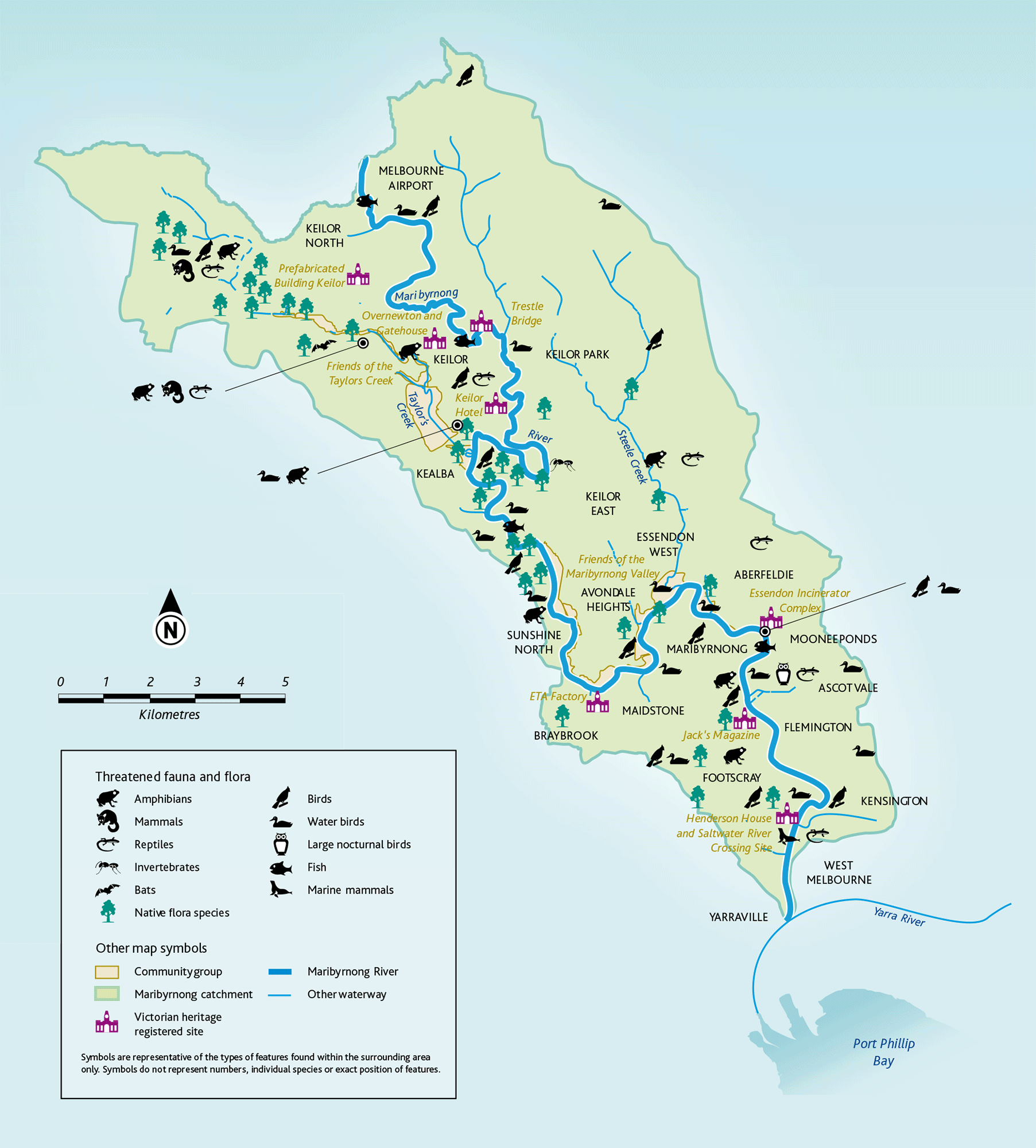

It has two main branches, Deep Creek and Jacksons Creek, which are fed by tributaries including Boyd and Konagaderra creeks.

Much of the area has been shaped by volcanic activity, as cooling lava formed sheets of basalt (bluestone). These formed steep banks as the river cut through the plain, and have given the western suburbs their characteristic flatness.

Only about ten percent of the river’s catchment area retains its natural vegetation. The remainder is agricultural (about 80 percent) and urban, with most development in Greater Melbourne and the larger rural townships.

Wildlife

The river and surrounding areas are home to a range of animals. One of the more interesting locals is the shy Black Wallaby, attracted by the ample water supply and efforts to restore its natural habitat – including coarse shrubs, bushes and grasses.

Other inhabitants include:

- Fish: a large proportion of native fish have been found, including four migratory species that use freshwater habitats and the downstream estuaries or ocean at different life stages.

- Birds: the river is home to at least 100 species of native and migratory birds, some of which travel from as far away as Japan, China and Korea. Waterbird species found in large numbers include the Pacific Black Duck, Chestnut Teal, Straw-necked Ibis, Purple Swamphen and Masked Lapwing.

- Frogs: although more likely to be heard than seen, the region has recorded about 12 species of frogs and toads – including the endangered Growling Grass Frog.

- Mammals: mammals include 10 species of bat, platypus, koalas, kangaroos, wombats, sugar gliders and even the Short-beaked Echidna. Other native mammals include Brushtail and Ringtail Possums, and the rakali (water rat).

- Reptiles: about 20 reptile species – mostly skinks – live in the area. Others include dragons, snakes, geckos, blue-tongue and legless lizards, and the Common Long-necked Turtle.

- Waterbugs: the river contains more than 60 species of aquatic insects, concentrated in the environments that best suit them. For example, shredders are mainly found upstream where most leaf litter falls.

- Plants: more than 290 species of flora can be found within 50 metres of the river. They play an important part in maintaining its vast ecology: trees provide homes and nesting places for birds and mammals, while also providing an important food source.

For an in-depth look at plant and animal species you might find, view our wildlife guide:

Places to visit

The river has plenty to offer nature lovers and fans of the outdoors, from boating and fishing, to cycling and walking along the 25-kilometre Maribyrnong River Trail.

Notable parks include:

- Brimbank Park (Keilor East), where native grasses can be seen along the river

- Footscray Park (Maribyrnong) – listed on the Victorian Heritage Register for its aesthetic, horticultural and social significance

- Pipemakers Park (Maribyrnong) – home to Melbourne's Living Museum of the West, which focuses on the area’s industrial, environmental, social and Aboriginal history.

Protecting the river

Like all waterways in the catchment, the Maribyrnong has extended periods of low flows. Flow patterns have been altered by human activity, as water is taken for domestic and agricultural use, and urban development generates more stormwater run-off.

Many native plants have disappeared, and introduced species like willows and blackberries now dominate the river.

Community champion: Ian Taylor – member of Sunbury Landcare Association and long-term volunteer at Organ Pipes National Park

“I have had a lifelong interest in the natural environment, and have had a wonderful and satisfying time working on the Maribyrnong River with like-minded people and sharing knowledge with them.

“The biggest challenges for this waterway are low flows resulting from the drought and too many dams and pollution. People must be mindful that their daily activities can contribute to pollution of the river.

People play a major part in ensuring that the Maribyrnong remains a place of natural beauty and somewhere that people can enjoy. Volunteering in a ‘Friends of’ group or holding working bees with family and friends are great ways of getting involved.”

You may also like...

Rivers and creeks

Rivers and creeks are central to everyday life, sustaining a complex ecosystem of plants and animals – and providing natural spaces for people to enjoy. Get to know some of Melbourne’s major waterways and the vital role they play.

Grants

Learn about grants available to support innovation, liveability and collaboration across water management, and improve river health.

View annual progress towards 10-year targets for waterways in the catchment, as set out in the strategy.