Mention the Yarra River and you might think of the last few kilometres that cut through the city – but it’s so much more. This iconic river flows 242 kilometres from its source on Mt Baw Baw in the Yarra Ranges National Park, north-east of Melbourne, all the way to Port Phillip Bay.

Melbourne’s most valuable natural asset is home to a range of beautiful indigenous plants, animals, birds and fish, and is vital to our social and economic wellbeing:

- as the source of 70 per cent of Melbourne’s drinking water

- in supporting productive agriculture

- providing recreational opportunities like rowing, fishing, bird watching, picnicking and walking.

Get to know the river:

History

The Wurundjeri people have always had a deep connection to the river. It provided many resources and important places for spiritual and community activity, like birthplaces and ceremonial and burial grounds. Many cultural sites are still with us today – like the Yarra Flats dreaming, and the Heide Scar tree and Bolin Bolin Billabong in Bulleen.

In 1835, Tasmanian farmer John Batman claimed he had bought the river and surrounding land from the Wurundjeri people in exchange for goods. But the Wurundjeri believed that they had simply taken part in a friendship ceremony, and were granting Batman leave to pass through their country.

By the following year almost 200 Europeans had settled on the river’s banks, growing to 500,000 people by 1860 once gold was discovered at one of the river’s tributaries in Warrandyte. ‘Enthroned by gold’, Melbourne quickly became Australia’s largest city.

But this growth came at a cost. In a town without sewerage or waste disposal, the formerly pristine Yarra soon became one of the world’s dirtiest rivers – a place to dispose of all things foul. Its waters spread diseases like diphtheria, dysentery, typhoid and scarlet fever, until the Werribee Farm was built to treat sewage in 1897.

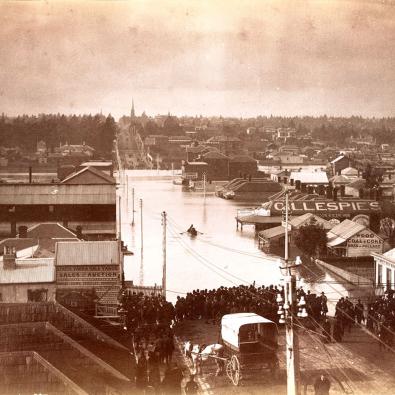

Devastating flooding was also a regular feature of the original narrow, twisting waterway. The first flood was recorded in 1839, and the largest in 1891 – which saw water levels rise 14 metres above normal, destroying 200 houses. To protect the city from flooding, a series of works began in 1879 to widen and straighten the river.

Did you know: Originally called Birrarung, meaning ‘a place of mists and shadows’, the river only became known as the Yarra in the 1830s – after a surveyor misheard local Aboriginal people saying Yarro Yarro: ‘it flows’.

Natural features

The Yarra River crosses an enormous range of habitats – from pristine forested catchments, to a range of agricultural lands and onto dense urban areas:

- The upper Yarra and its main tributaries flow through forested, mountainous areas that have been protected for over 100 years to safeguard the quality of our drinking water.

- The middle and lower sections have been mostly cleared for agriculture and urban and industrial development, eroding the clay soils and resulting in the river’s muddy colour.

- The lowest section of the Yarra is an estuary, where salt water from Port Phillip Bay travels about 10 kilometres upstream.

The stretch of the Yarra River between Warburton and Warrandyte has been identified as a Victorian Heritage River. Watch the following video to see it for yourself:

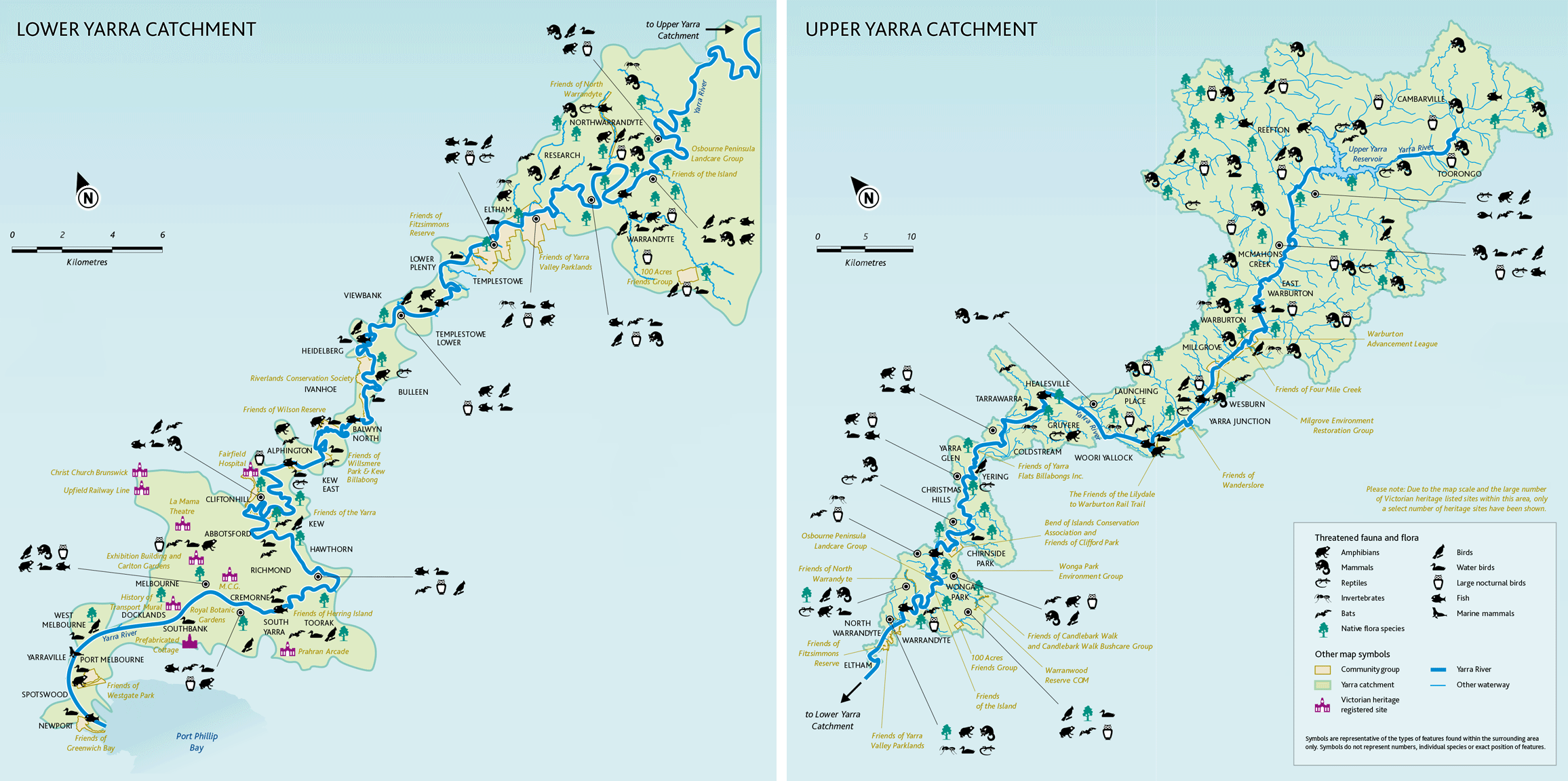

Did you know: More than one-third of Victoria’s population lives in the Yarra catchment, which spans about 4000 square kilometres.

Plants and wildlife

Thanks to an abundance of native plants and water supply, the wildlife in and around the Yarra River is highly diverse. One-third of Victoria’s animal species are found in the Yarra catchment, including:

- Fish: high-quality habitat supports a diverse community of fish, though native species face competition from those that have been introduced. Barriers (such as weirs) pose another challenge, blocking upstream or downstream migrations needed to fulfil their lifecycle.

- Birds: over 190 species of birds feed and nest along the river, including insectivorous, honeyeaters, birds of prey, seedeaters, songbirds and waterbirds. The laughing kookaburra is an iconic species, and some – like the White-faced Heron and Nankeen Night Heron – are classified as regionally significant.

- Frogs: many parts of the river provide perfect frog habitat, with plenty of diverse wetlands to breed, feed and shelter from prey. Notable species include the eastern froglet, Peron’s tree frog, southern toadlet and the dwarf tree frog.

- Mammals: 38 mammal species are known to live within 50 metres of the Yarra, many of which make their homes among the tree hollows that line the river. These include bats, gliders, bandicoots and other iconic species – such as the koala and the eastern grey kangaroo, which can be found feeding along the riverbank.

- Reptiles: skinks, turtles, snakes and lizards are known to inhabit the river, and can often be found sheltering among leaf litter, grasses, rocks and logs. The iconic Eastern Long-necked turtle can be seen in still water bodies such as lakes and billabongs.

More than 25 unique vegetation communities make their home along the river and its billabongs, wetlands and swamps:

- Riparian scrub occurs along much of the river. River red gums form a tree canopy with a dense understorey of silver wattles, river bottlebrush, prickly currant bush and tree violet. Rushes and sedges often line the banks.

- Swamp scrub occurs in permanently wet areas, especially in the catchment’s south and east.

- Native grasses provide food for parrots, wombats, wallabies and kangaroos. Once vast, they are a precious and fragile resource and vulnerable to introduced grasses, soil disturbance, grazing, mowing and fertilisers.

- Manna gums can be found along the river’s upper reaches, and are an important food source for koalas.

For an in-depth look at plant and animal species you might find, view our wildlife guide:

Places to visit

In recent decades, developments such as the Victorian Arts Centre, Southbank, the Exhibition Centre, Federation Square and Docklands have transformed the waterfront. Today, the Yarra River is an integral part of our lives and each year attracts millions of visitors – who walk, ride, row, fish or camp along its banks.

Following the course of the river is the 38-kilometre Main Yarra Trail, which stretches from Southbank to the north-eastern suburbs through river flats, sporting ovals, market gardens and paddocks. Some of the parks you’ll see along the way include:

- Birrarung Marr (Melbourne) – this scenic riverfront park in the heart of Melbourne hosts some of the city’s biggest events and festivals, including the Moomba Waterfest each March.

- Domain Parklands (Melbourne) – on the south bank of the river, this patchwork of 123 hectares of parks and gardens includes popular destinations such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Shrine of Remembrance and Sidney Myer Music Bowl.

- Warrandyte State Park (Warrandyte) – Melbourne’s closest state park is a haven for picnickers, bushwalkers, canoeists, birdwatchers and those seeking peace and solitude.

- Westerfolds Park (Templestowe) – this 120-hectare metropolitan park has conserved 400 native plant species and is a popular spot for picnics and family gatherings.

- Yarra Bend Park (Fairfield) – inner Melbourne's largest natural bushland park attracts 1.5 million visitors a year to explore its open woodlands, formal parklands and historic boathouses and trails. Its best-known feature, Dights Falls weir, was built in the 1840s to provide water to one of Victoria’s first flour mills.

Protecting the river

The Yarra has greatly improved since the 1970s and 80s, thanks to an expanding sewerage system servicing Melbourne’s industry and suburbs. The river now compares favourably with many metropolitan rivers overseas.

However, it still faces a number of challenges:

- Water quality is good in the upper catchment but deteriorates downstream, due to agriculture, urban development and the resulting stormwater pollution.

- Flows in the Yarra and its tributaries have been significantly altered by numerous dams and the extraction of water for agriculture.

- Habitat loss has slowed in recent years thanks to revegetation, erosion control and removal of fish migration barriers. Some animals, like platypus, have been rediscovered in areas where they had disappeared.

Many community groups and schools are involved in looking after river, but we all have a part to play.

Did you know: Each year, volunteers spend an incredible 50,000 hours working in parks along the Yarra.

Community champion: Ian Penrose – founder, Yarra Riverkeeper Association

‘[At the Yarra Riverkeeper Association] our activities include monitoring the health of the Yarra and any developments through our regular boat patrols, water testing, speaking with river stakeholders, running community forums and tours, publicising and educating the public, schools and others while supporting other community groups and authorities that help the river.

The community and authorities need to come together to take a closer interest in the Yarra’s ecology. It’s up to all of us to play our part to protect this special natural resource for generations to come.’

You may also like...

Rivers and creeks

Rivers and creeks are central to everyday life, sustaining a complex ecosystem of plants and animals – and providing natural spaces for people to enjoy. Get to know some of Melbourne’s major waterways and the vital role they play.

Grants

Learn about grants available to support innovation, liveability and collaboration across water management, and improve river health.

Burndap Birrarung burndap umarkoo (Yarra Strategic Plan)

The 10-year plan supports collaborative management of the Yarra and its lands to give effect to the community’s long-term vision.

View annual progress towards 10-year targets for waterways in the catchment, as set out in the strategy.